Neck

Lab Summary

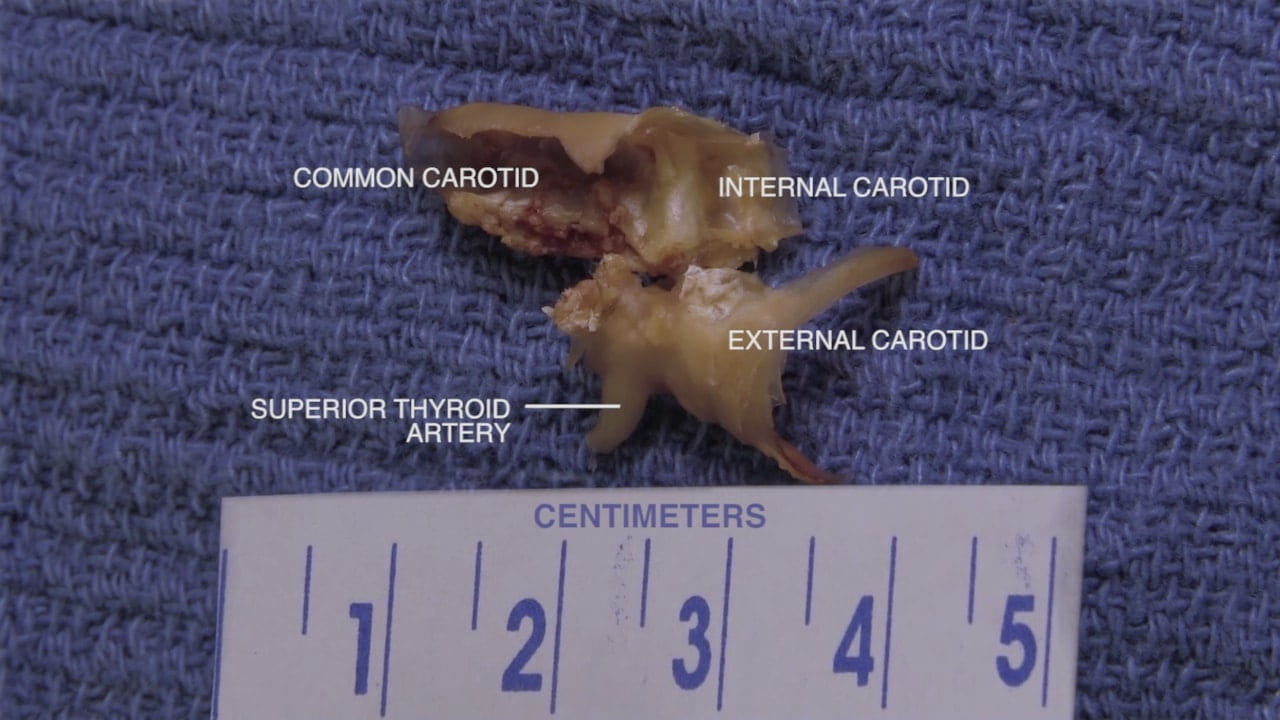

The anatomic continuity from chest to neck to face and head including great vessels, airway and esophagus are explored. Critical innervations are shown in detail along with musculature and glandular structures. Finally, a carotid endarterectomy is show since this is such an important location for significant arteriosclerotic disease and stroke.

Lab Objectives

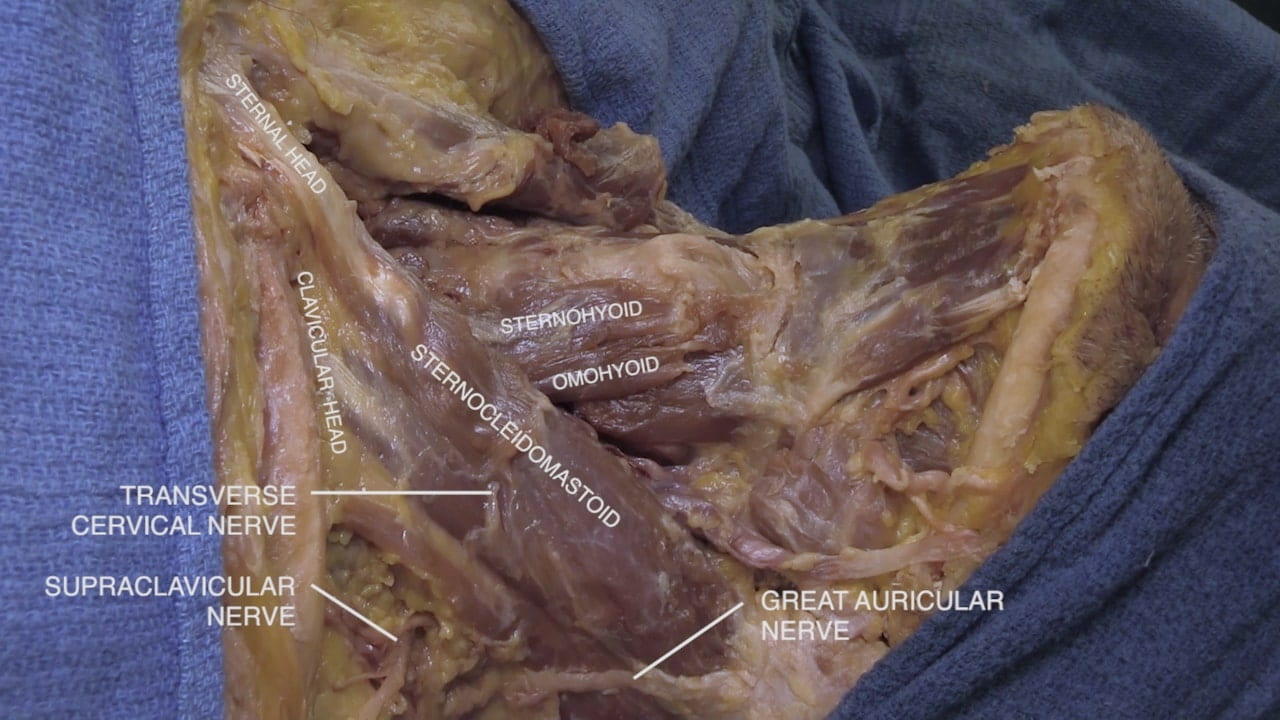

- Describe the position and importance of internal and external jugular veins.

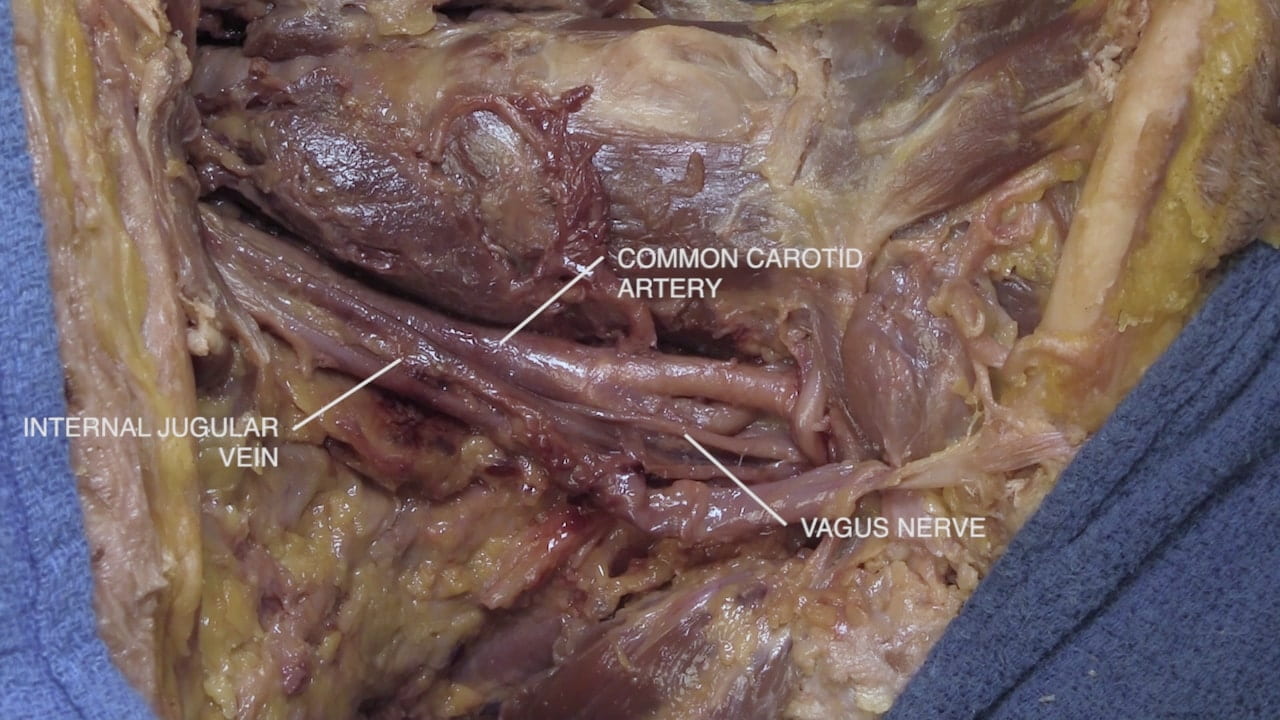

- Describe the contents and relations within the carotid sheath.

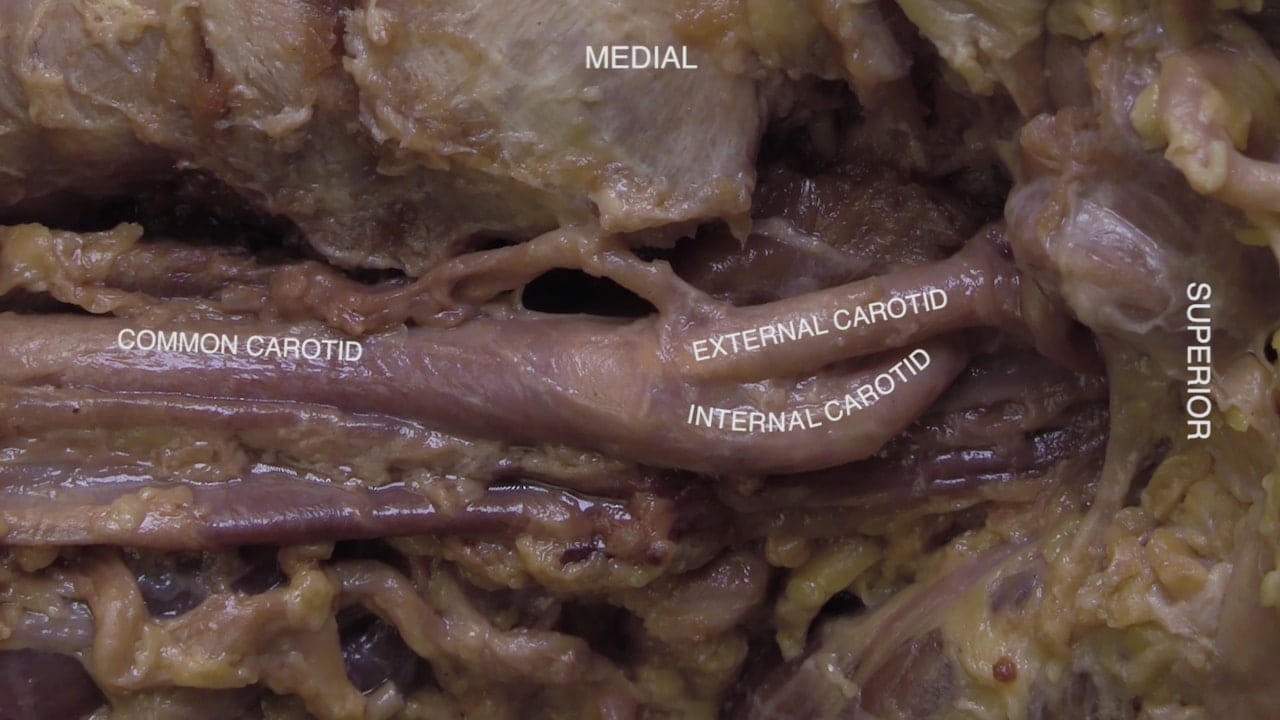

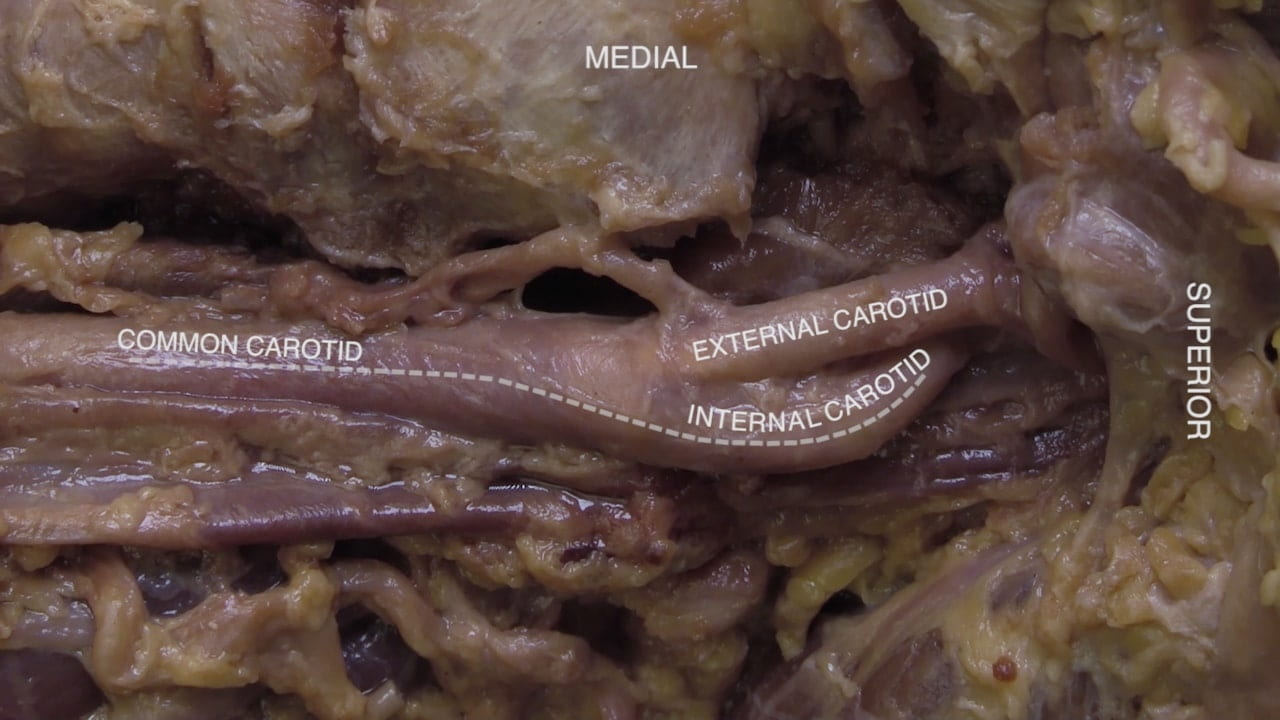

- Describe the location of the carotid bifurcation.

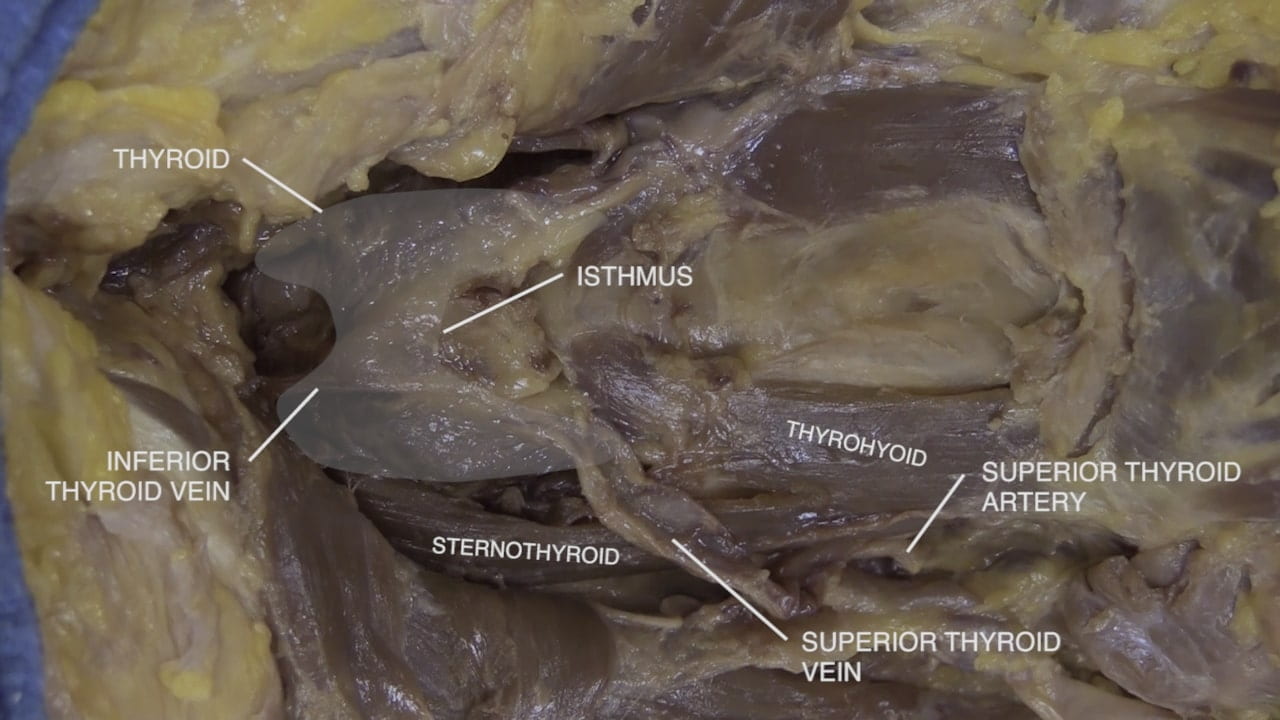

- Describe the position the thyroid gland including the isthmus.

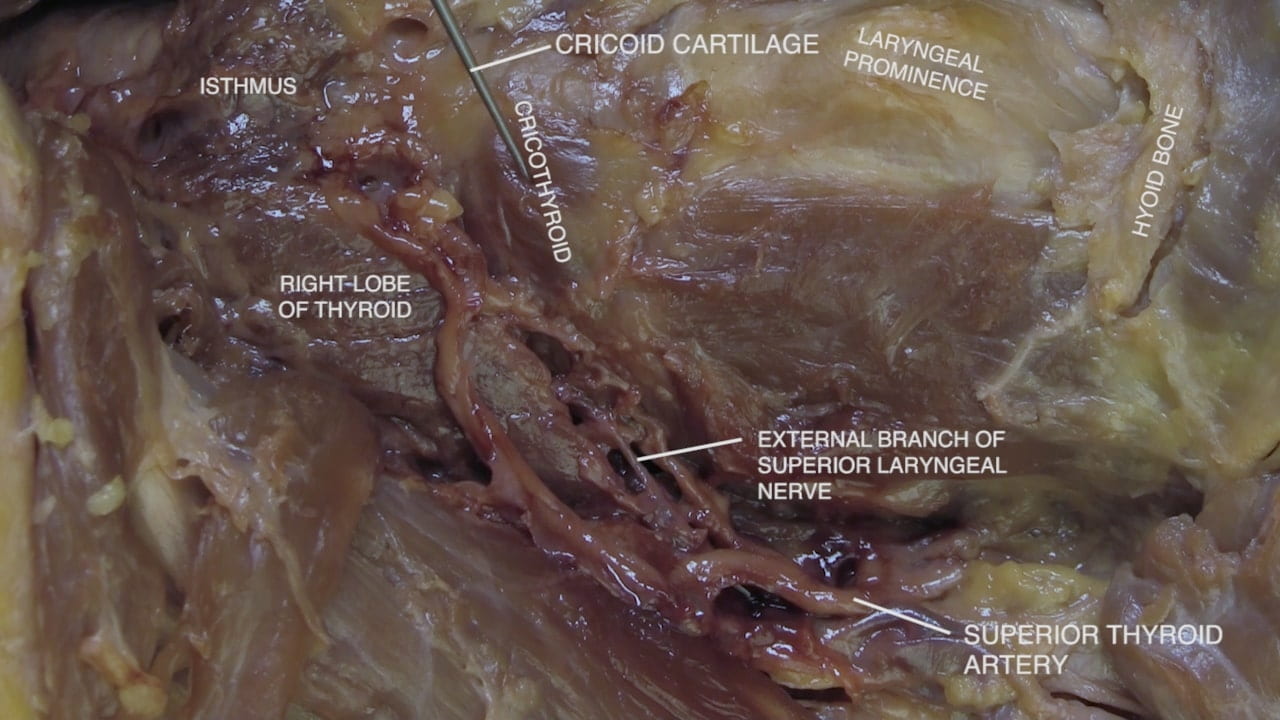

- Describe the arterial and venous circulation for the thyroid gland.

- Describe the course of the recurrent laryngeal nerve in the neck.

- Describe the relationship of the airway and esophagus.

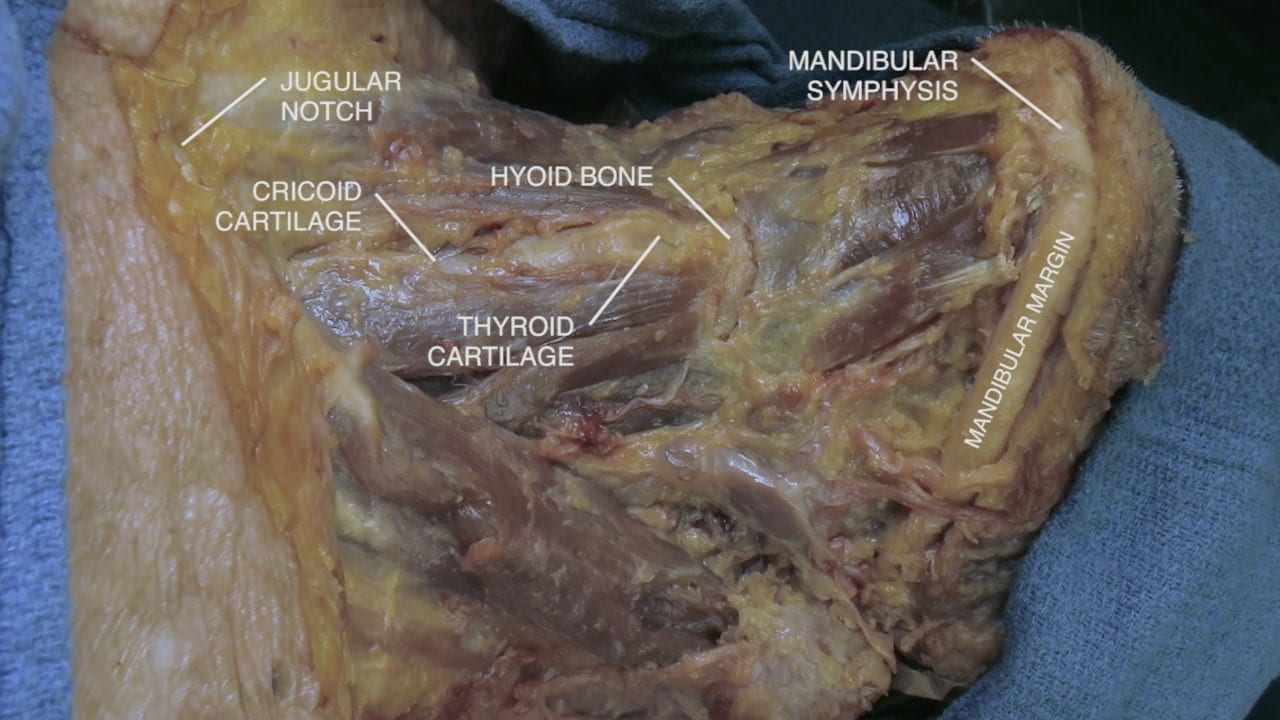

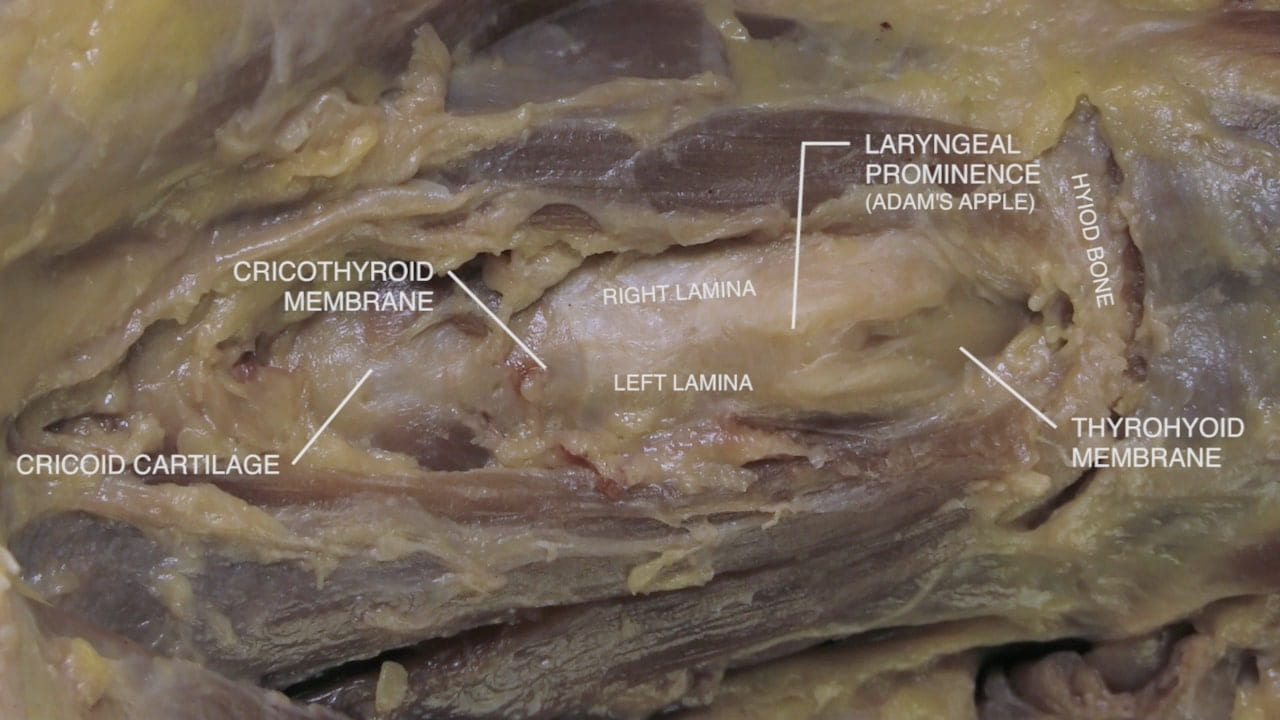

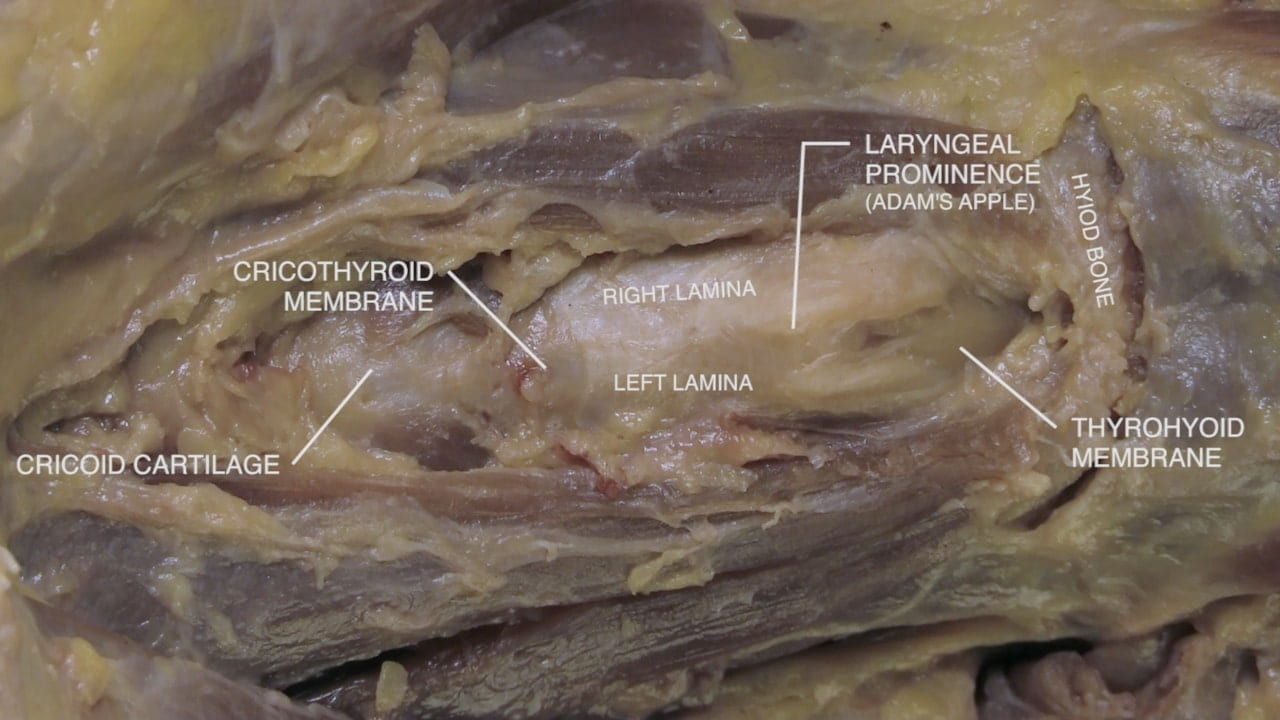

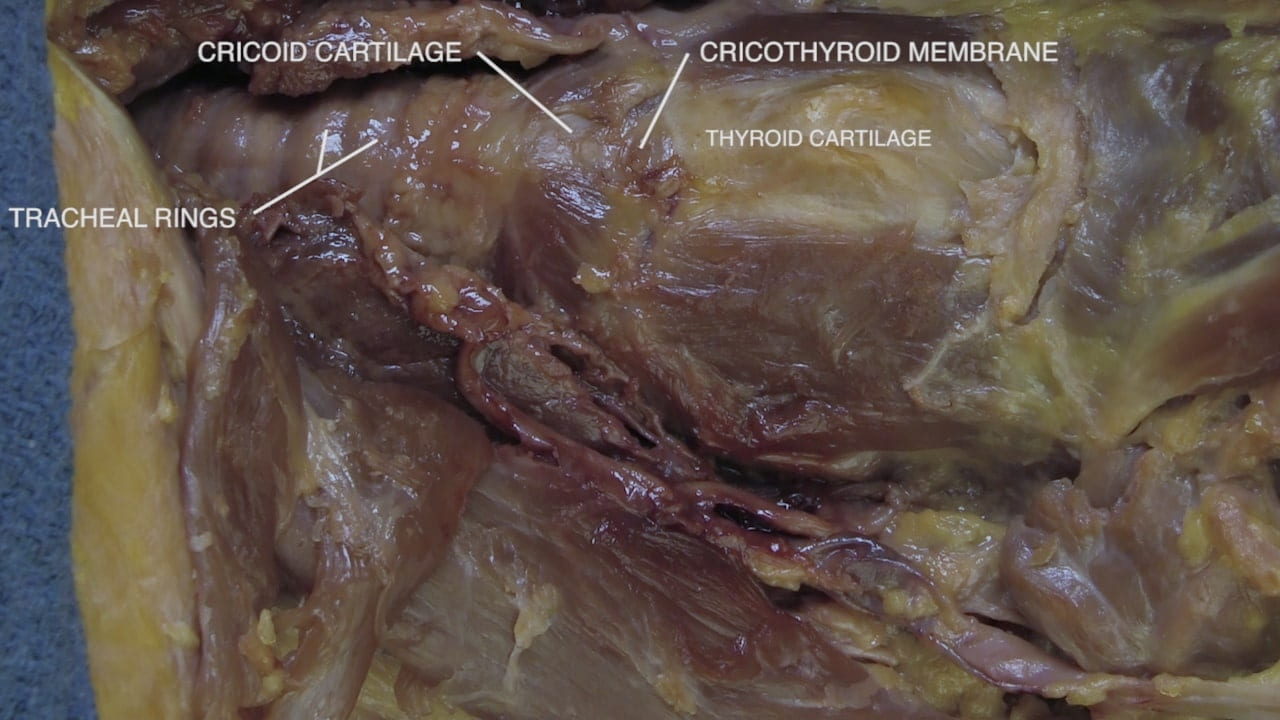

- Describe the positions of the hyoid bone, thyroid cartilage, cricothyroid membrane, cricoid cartilage and tracheal rings.

- Explain the placement of an emergency airway.

Lecture List

Neck Part I (Superficial), Neck Part II (Deep), Carotid Endarterectomy

Neck Part I

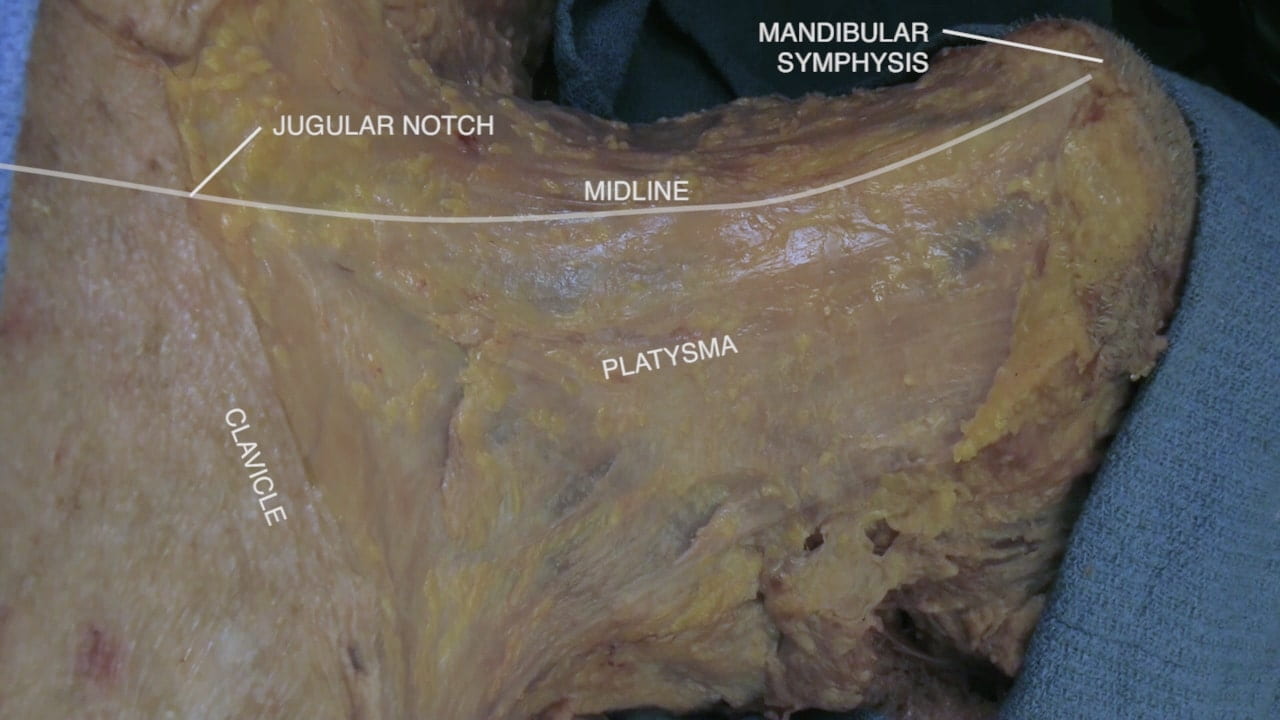

Skin Incisions and Midline Neck

Thyroid Gland

Neck Part II

Carotid Sheath

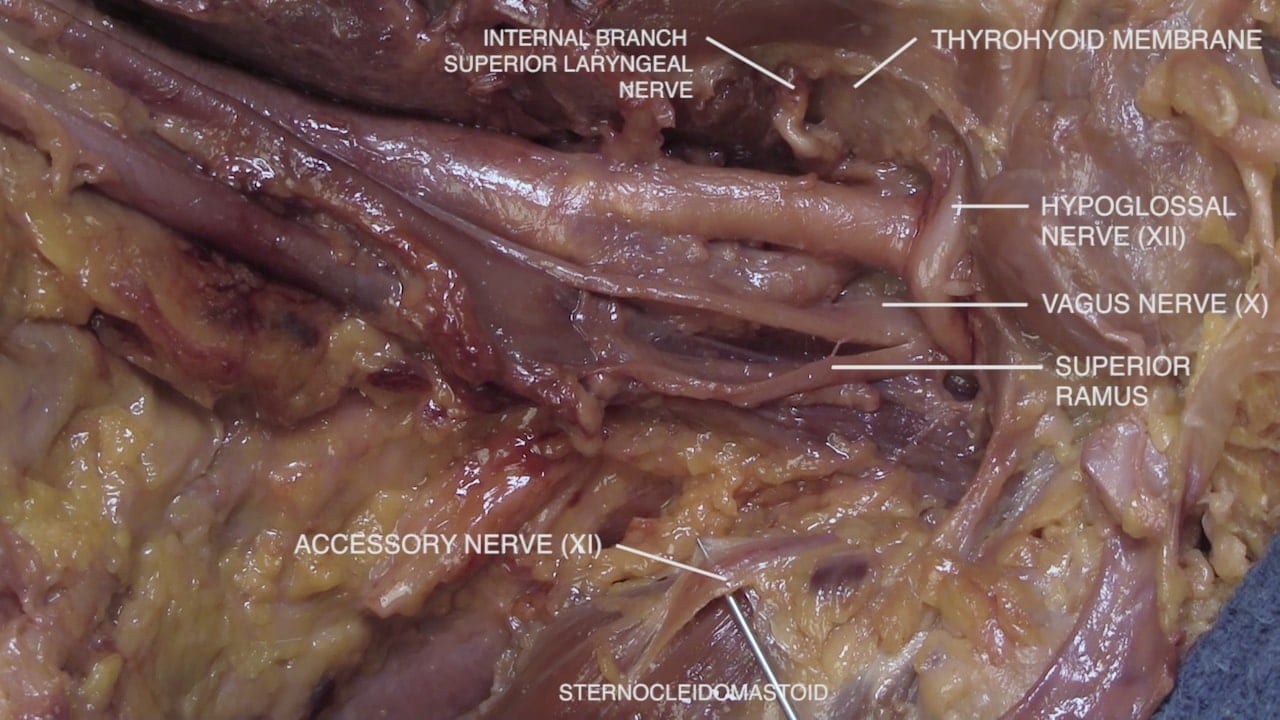

Lower Cranial Nerves

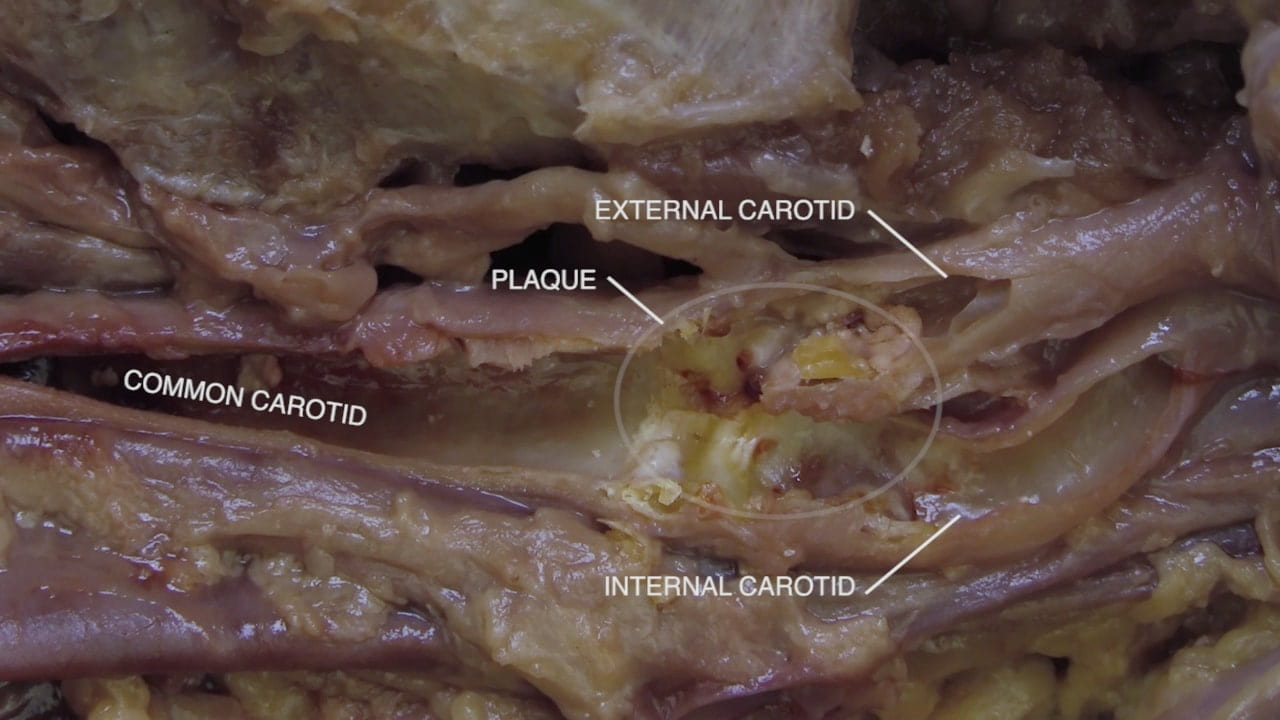

Carotid Endarterectomy

Carotid Endarterectomy

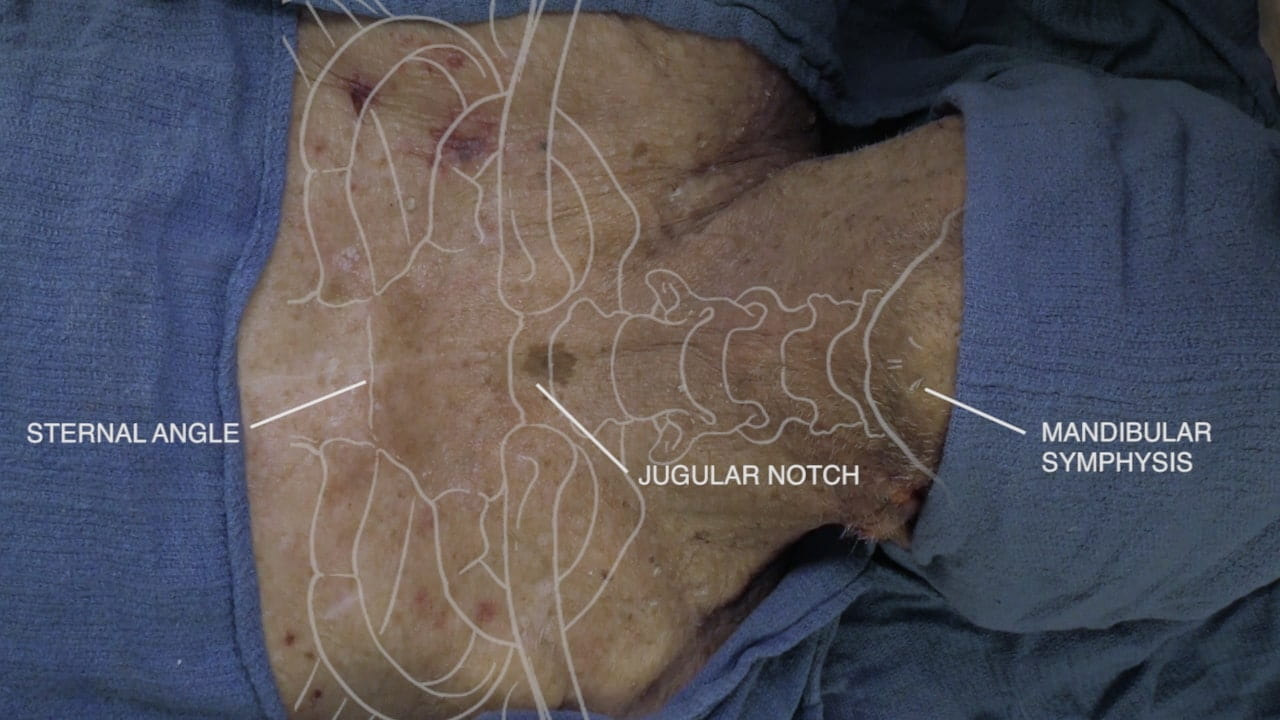

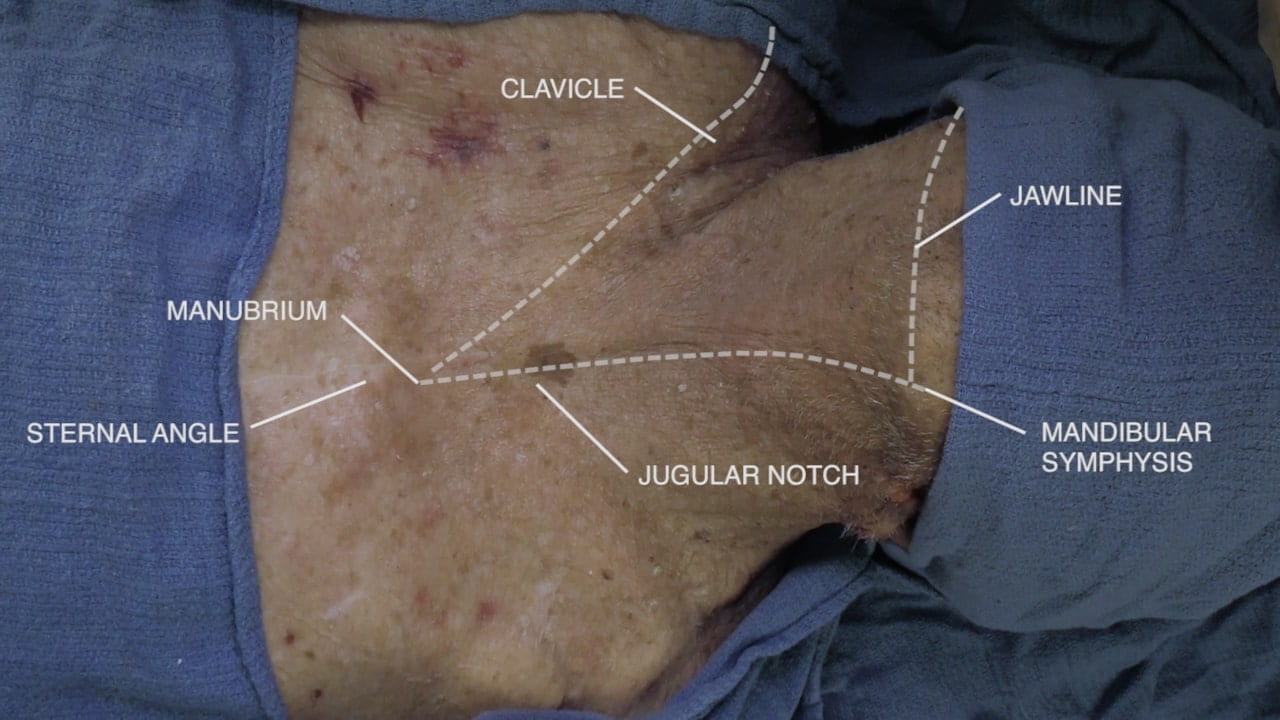

Neck Surface Anatomy

Physical Examination of the Neck

Neck Clinical Correlations

Trauma/EM: Airway Compromise: If a patient’s airway is compromised (e.g., due to anaphylaxis or trauma) and oral intubation cannot be successfully obtained (a can’t intubate, can’t oxygenate scenario), an emergency airway will be pursued, most commonly via a cricothyrotomy. A skin incision is made to access the cricothyroid membrane (palpated between thyroid and cricoid cartilage); an incision is then made in the cricothyroid membrane through which an airway can be installed.

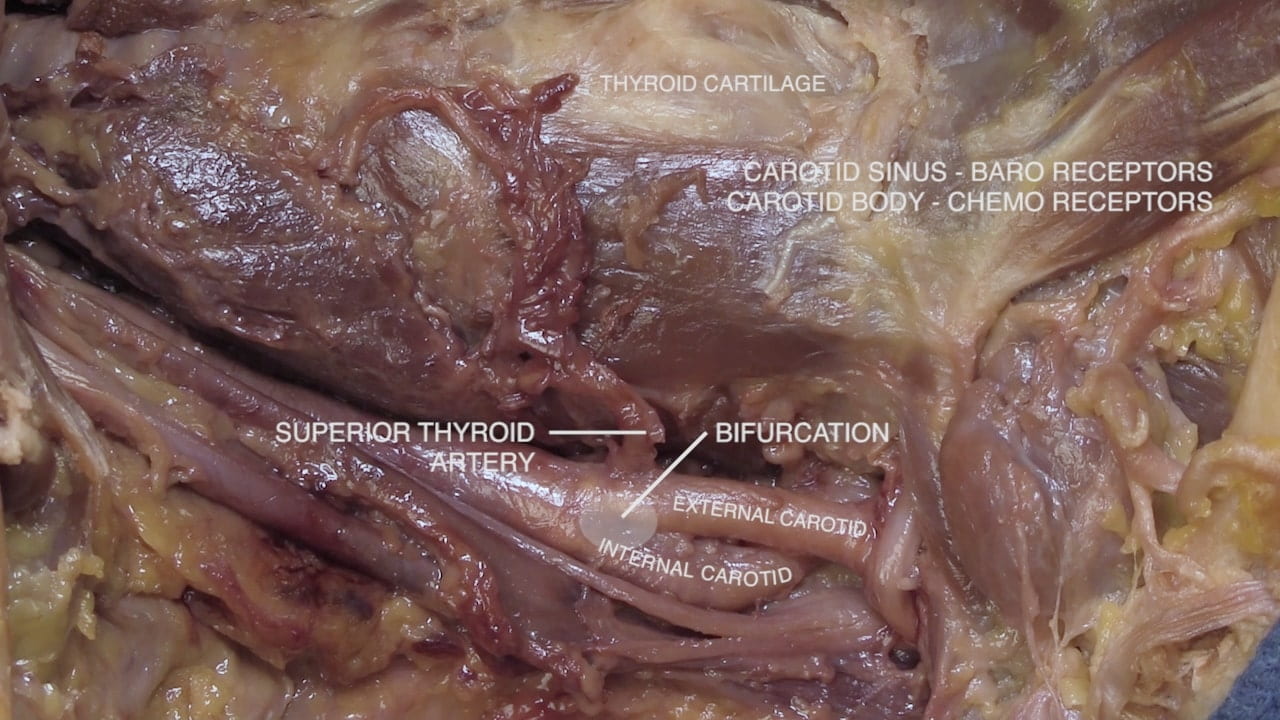

Procedure: Carotid Artery Stenosis; CEA versus TCAR: Carotid artery stenosis (narrowing) is most commonly due to atherosclerosis. Plaque burden tends to be largest at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery into the internal and external carotid arteries (why?). Carotid artery stenosis is often asymptomatic but may be symptomatic if disruption of cerebral blood flow is severe enough. Alternatively, small pieces of the plaque can break off (embolize) and enter the brain causing transient-ischemic attacks (“mini strokes”). In symptomatic cases, stabilization or removal of the plaque is critical. Traditionally, carotid artery plaques are removed through carotid endartectomy (CEA), whereby the carotid artery is incised and the plaque removed. During CEAs, small pieces of the plaque can embolize, therefore peri-procedural stroke is a feared complication. Alternatives to CEA are carotid stenting and, more recently, transcarotid artery revascularization (TCAR), both of which deploy an intravascular stent. TCAR carries a lower risk of stroke because blood flow direction in the carotid artery is temporarily reversed prior to stent deployment thus preventing embolization distally to the brain.

Embryology: Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF): The trachea and esophagus develop from a common primitive foregut, explaining their anatomical proximity. At the 4-5th week of development, a tracheal bud arises from the foregut. This bud continues growing and a tracheoesophageal septum arises to separate the dorsal esophagus from the ventral trachea. If this septum does not correctly develop, an inappropriate communication (fistula) between the trachea and esophagus remains. Coughing (Ono’s sign), choking, difficulty breathing, and cyanosis during feeding or swallowing (why?) are key diagnostic indicators of TEF. Pneumonia secondary to aspiration of food content is also common. Movement of air from the trachea into the digestive tract can cause abdominal distention. TEF is commonly comorbid with other birth defects (see VACTERL association). Surgery is usually required to allow uncomplicated feeding. TEFs are generally embryological in origin but can be acquired secondary to post-intubation trauma, chronic infections, radiation injury, and post-surgical complications.

Surgery/Autopsy: Thyroglossal Duct: Thyroid development begins at ~2-3 weeks at the foramen caecum, the region between the anterior 2/3rd and posterior 1/3rd of the tongue. From this region, the thyroid travels to its final destination in the neck via the thyroglossal duct by week 7. In ~50% of individuals, the distal portion of the thyroglossal duct will become the pyramidal lobe of the thyroid. The remainder of the duct should obliterate by week 10. If a region of the thyroglossal duct persists, a thyroglossal duct cyst (TDC) can arise. TDCs present as a midline neck mass that move upwards with protrusion of the tongue or swallowing. To rule out other causes of neck masses, biopsy and imaging can be used for diagnosis. TDCs are removed surgically through a Sistrunk procedure: the skin and platysma are incised and elevated. The strap muscles are retracted laterally to reveal the TDC, which is dissected free from surrounding tissue. TDCs can be closely associated with the hyoid bone therefore dissection is done until the cyst is pedicled by the hyoid bone. The hyoid bone is cut on each side of the midline and dissection continues into the posterior hyoid space towards the base of the tongue (this removes the foramen caecum as well). The goal of surgery is complete removal of the TDC and remaining duct tissue to prevent recurrence. Attention to laryngeal cartilages and other landmarks is critical to preventing airway damage. Surgical video: doi.org/10.1002/lary.29840.

Anatomical Variations: Carotid Artery Bifurcation: The level at which the common carotid artery branches into the internal and external carotid arteries can vary quite a bit. The classical bifurcation site is noted to be between level of C3 and C4 (near the laryngeal prominence; ~50% of population). However, bifurcation can occur at any cervical level. Bifurcation occurring above C3-C4 levels (i.e, high-lying bifurcation) are typically located at the body of the hyoid bone (40% of the population) or the apex of the greater horn of the hyoid bone (~15%). Low-lying bifurcations can occur but are rarer. Knowing the location of bifurcation is critical for safe dissection during surgical procedures in the neck (e.g., vascular procedures, lymph node removal, anterior approach to spine, etc.)

Imaging: The neck can be imaged with many modalities. Plain X-ray is often used for pediatric patients when trying to evaluate the airway or look for a foreign body. For adults, CT of the neck with IV contrast is one of the best ways to evaluate the soft tissues of the neck for entities such as neck tumors, infection or lymphadenopathy (and can be used with pediatric patients when appropriate). MRI can also be performed for soft tissue evaluation. Both CT and MRI can also be protocolled to focus on the vessels (for example CTA or MRA of the head and neck to look at the arteries, “A” is for angiography) or to focus more on osseous abnormalities of the C-spine, such as degenerative changes or trauma. MRI is the best modality when evaluating the nerve structures such as the spinal cord or nerve roots of the neck, and we will see more examples of this when evaluating the anatomy of the central nervous system.

Imaging Correlate: Head to Table 8 to see a CTA of the neck and correlate anatomy for the great arteries of the neck!

Images (Click to Enlarge)

Thyroglossal duct cyst w/ papillary thyroid carcinoma obtained from male patient in his 40s. Left: gross specimen, middle: serially sectioned (note the cyst versus nodule), right: microscopic slide from specimen (note papillae w/ clear nuclei)